I was a big fan of Asterix and Tintin when I was a kid, and I live very near Panjiayuan, which has a large space dedicated to old books. Well, mostly old books. There are a few stalls in that space selling very new books, too. And so I was very happy when I discovered that among all these old books are many old comics, and among these many old comics are Chinese versions of Tintin books. And so I started buying Tintin books again, and so discovered a particular type of comic – the 小人书/xiǎorénshū that is actually pocket-size, in that each one could easily fit into a child’s pocket (how many “pocket-size” books would only ever be considered small enough to fit in a pocket if one were on a whole other planet inhabited by people 15 metres tall?). And I love these books.

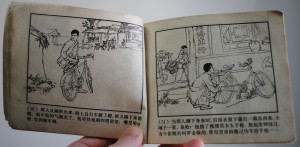

Partly it’s the format: The part of me that never grew much beyond 10 years old loves the thought of being able to slip a comic into my pocket, and run off to school able to pull it out and read it whenever I find a quiet moment (or the teacher isn’t looking – wait, I am the teacher – when the students aren’t looking). And one fairly simple black and white picture per page with a small amount of text – 2 or 3 sentences, usually – below makes for easy, bite-sized reading.

Oh wait, I just reminded myself of something else I really enjoyed as a kid.

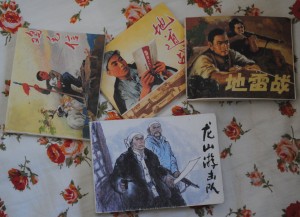

So I started exploring these comics and found, in addition to Tintin, quite a few just like those Commando Comics, but Chinese, presenting stories of the Anti-Japanese War. Now these stories I love.

But wait, they’re not all old. There are still books being printed in this format, as I discovered when my wife bought me this:

But wait, they’re not all old. There are still books being printed in this format, as I discovered when my wife bought me this:

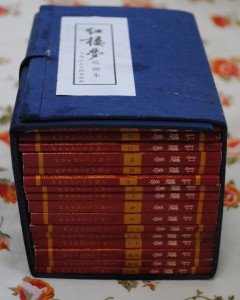

Yes, that is the 红楼梦, Dream of the Red Chamber, in 10 volumes. And:

Yes, that is the 红楼梦, Dream of the Red Chamber, in 10 volumes. And:

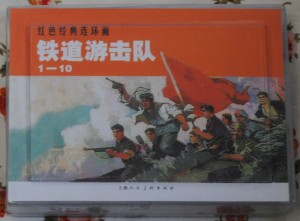

铁道游击队 – Railway Guerillas! Awesome! Again, a story told in 10 volumes, but unlike the cool, classical-looking blue cloth over (presumably) cardboard binder the Red Chamber comes in, these 10 volumes come in a plastic box.

铁道游击队 – Railway Guerillas! Awesome! Again, a story told in 10 volumes, but unlike the cool, classical-looking blue cloth over (presumably) cardboard binder the Red Chamber comes in, these 10 volumes come in a plastic box.

Now, quite a few of these stories do come in 10 volume sets – and getting a complete set at Panjiayuan can be quite a mission, as some of the book sellers just have a box of comics all loose and jumbled up. I once saw a guy trying to reconstruct the full 10-volume set of the Red Chamber – apparently the exact same edition that I have – from one such box, and it was quite a mission. But most of the stories are only one or two volumes, with two-volume stories often coming in a thin plastic sleeve. Rummaging through a box of loose, jumbled books can be quite fun in that you’ll often discover a range of unexpected things as you try to get the complete stories together, but the downside, of course, lies in the risk of missing or damaged volumes. Then again, those dealers who take care to keep the stories together and the books intact do slightly lower the chances of serendipity, and in one case last time I was at Panjiayuan one guy went a bit too far in having a complete set of Tintin stories tied in string ready for somebody willing to shell out a couple of hundred kuai. It was a reasonable price, but I already had half the stories in the bundle.

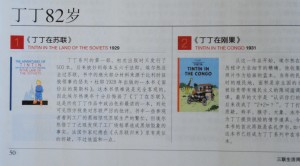

So back to Tintin: I was quite surprised to read Bruce Humes’ post about there being no Chinese translation of Tintin in the Land of the Soviets (although Jock 123’s comment to that post at least partly explains why I’ve never seen a copy in any language), because just before I’d read Bruce’s post, I had seen in the November 7 issue of 《三联生活周刊》 this:

Now, I am absolutely not questioning the veracity of Bruce’s post in any way. The two pictures above are of English-language editions of Tintin stories, and I see nothing in the text to suggest Tintin in the Land of the Soviets has been translated into Chinese. But it was a bit of a surprise to come across Bruce’s post having just read a magazine article not only mentioning, but picturing the very book Bruce was writing about. And actually, not only do I see nothing in the text in the picture above to suggest Tintin in the Land of the Soviets has been translated, I also see nothing to suggest it has. The magazine article is simply about the Tintin stories.

Now, I am absolutely not questioning the veracity of Bruce’s post in any way. The two pictures above are of English-language editions of Tintin stories, and I see nothing in the text to suggest Tintin in the Land of the Soviets has been translated into Chinese. But it was a bit of a surprise to come across Bruce’s post having just read a magazine article not only mentioning, but picturing the very book Bruce was writing about. And actually, not only do I see nothing in the text in the picture above to suggest Tintin in the Land of the Soviets has been translated, I also see nothing to suggest it has. The magazine article is simply about the Tintin stories.

But what I do see are two books in English. Indeed, every Tintin story listed in that article is given with Chinese and English titles and a picture of the English book. Now, I remember being surprised in a no shit Sherlock kind of way when I first realised that the Asterix and Tintin books I had grown up reading were translations from French. Foreign language books are hard to find in New Zealand, I grew up in a monolingual family, and when one is enjoying funny and exciting stories as a wee lad, one does not stop to ask which country they came from and what language they were written in. In fact, remembering some of my childhood confusion about certain aspects of the travel portrayed in The Black Island, I think I probably just assumed that, like so much of what I read as a lad, these books had come from Britain. Anyway, those pictures of the English editions in a Chinese magazine serve to reinforce an impression I got when I first started reading the Chinese versions of Tintin: The Chinese versions are translated from the English. Translations of translations. The first hint was the translation of Tintin’s dog’s name: 白雪/báixuě – Snowy. Milou in the original French. And there’s the other characters’ names, too. And then I got to thinking: Surely Tintin, based on the French pronunciation, would be more accurately transliterated as 单单 (or perhaps some more fortuitous rendering that would equally come out as dāndān (or just as good, perhaps, tāntān)) rather than 丁丁 (dīngdīng)?

I don’t think it really matters which language Tintin was translated from – this is not poetry we’re talking about. But really, is China so completely obssessed with English that nobody could be found to translate these books from the French? French is not exactly an obscure language. But wait… how many times have I heard 外语 (foreign language) used as a synonym for 英语 (English)? Right.

But back to the Chinese books: Two of my favourites, surprisingly enough given how much I hate TV, I actually discovered via TV. One is the Railway Guerillas, pictured above, and the other, my favourite, is 小兵张嘎/Little Soldier Zhang Ga:

I first came across this story, like the Railway Guerillas, in the form of a recent TV series adaptation. Then my wife introduced me to the 1963 film. Then I found the comic. But where the TV series tends to highlight the comedic aspect of a mischievous kid fighting back against cruel, but often bumbling, Japanese invaders, the film and comic tend to take a more serious look at an orphaned child in time of war and occupied territory dealing with the death of his grandmother at the hands of the occupiers by joining the resistance. And apparently its based on a true story.

I first came across this story, like the Railway Guerillas, in the form of a recent TV series adaptation. Then my wife introduced me to the 1963 film. Then I found the comic. But where the TV series tends to highlight the comedic aspect of a mischievous kid fighting back against cruel, but often bumbling, Japanese invaders, the film and comic tend to take a more serious look at an orphaned child in time of war and occupied territory dealing with the death of his grandmother at the hands of the occupiers by joining the resistance. And apparently its based on a true story.

And it occurs to me that there are some serious questions that could be asked about the presentation of events, protagonists, and values in these comics that could be posed. Questions of racism and anti-semitism in Tintin have been thoroughly discussed, after all. Zhang Ga is interesting in how it brings childhood into war, and war into childhood. But to be honest, I’ve just been enjoying them.

#1 by Ji Village News on November 21, 2011 - 1:08 pm

I love those 小人书. During my day we called it 画书 in my hometown. (As an aside, 书 is pronounced as “fu” in 鲁南/苏北土话. 鲁南 dialect tends to replace the consonant “sh” with “f”, among other characteristics. For instance, the 鲁南 native way of saying 水 is “fui”, although those ways of pronunciation are dying fast.) I will try to make a trip to Panjiayuan next time I am in Beijing to see what treasures I can find.

We enjoy Asterix and Tintin as well, courtesy of the Swede in the family. Once again thanks to my wife, we also enjoyed Moomintroll greatly. In fact I think my son has named Moomintroll as the most influential book in his life so far! I wonder if Moomintroll series was translated into Chinese, pity if it wasn’t.

Oh well, call me biased, but I enjoyed reading the English translation of Astrid Lindgren’s books when my son was little, not just Pippi Longstocking: humorous, whimsical, and has a certain, and appropriate depth to it. In fact I should dig some out again to re-read!

#2 by wangbo on November 21, 2011 - 1:39 pm

Interesting, I hadn’t heard of “sh” becoming “f” before. It’s also interesting that you say “those ways of pronunciation are dying fast.” I have students who’ve told me their parents simply didn’t teach them the local dialect, only Putonghua, and I’ve heard of similar things happening elsewhere.

I hadn’t heard of Moomintroll, although Wikipedia makes it sound cool. I’m curious, though: Have you ever seen Asterix in Chinese? Wikipedia lists Mandarin as one of the languages it’s been translated into, but I have never seen it here.

Panjiayuan I am very wary of these days. It’s changed a lot over the years and become very touristy in some respects. One positive change, though, is that it’s now open weekdays instead of weekends only. The book stalls, though, well, there’s not much you can do to ruin a bookstall, and piles of secondhand books mean endless fascination.

#3 by Ji Village News on November 22, 2011 - 12:24 pm

No, I have never seen Asterix in Chinese. From Roland Soong’s weibo, a publisher is looking for a translator now:

http://publish.dbw.cn/system/2011/11/06/053494793.shtml

I will visit Beijing in early December. I will take some time to see my parents via the high speed train, and then may have a couple of days of free time in Beijing.

#4 by wangbo on November 22, 2011 - 12:37 pm

Interesting. I note they’re looking to translate from the French original, unlike all that Tintin which has come via English. I’ll definitely be buying Asterix when it comes out.

Stop by for a visit if you’ve got time in Beijing this trip.

#5 by Ji Village News on November 23, 2011 - 12:43 pm

Thanks mate.

Since I mentioned my dialect, I may as well offer a link to a video of a traditional 柳琴戏 from my home town, 喝面叶

http://www.tudou.com/programs/view/gWlgKaUatHo/

The narration and singing is done in 鲁南 dialect, which is very funny, and a definite classic, in my humble opinion. It was performed by a traditional opera troupe from a neighboring city, so the dialect is teeny-tiny different, but close enough to mine.

It may not be your cup of tea, but at least you will know what it tastes like! If you are so inclined, after watching the first part, follow the link to part 2.

The video is well-done. I have a secret wish that Zhang Yimou would turn a traditional comedy like this into a movie. I think he has what it takes to make it a good one.

#6 by wangbo on November 23, 2011 - 1:46 pm

I’m always keen to try new kinds of tea. Pity that Tudou made sure the ads were loud enough for my neighbours to hear, but the actual video was a tad on the quiet side and I took my good speakers out to the village. Nevertheless, I enjoyed it, and I see there’s plenty more, but I must get some work done…

Thinking of the music in 《黄土地》 (directed by Chen Kaige, I know, but Zhang Yimou’s cinematography) and 《红高粱》, and of his early films more generally, and of the incorporation of elements of 二人转 in 《三枪》, I think Lao Zhang probably could do something interesting with 柳琴戏. But his early films were made by a young man out to prove his virtuosity in less commercialised times, and 二人转 has Zhao Benshan, and looking at 《三枪》, one wonders what would become of 柳琴戏 if Lao Zhang got a hold of it. Hopefully he would manage to err on the side of “bloody good” rather than “err… nice try”.

Edit: And of course he’s directed Western operas, the Olympics opening and closing ceremonies, a ballet version of Raise the Red Lantern…

But I would also nominate 豫剧 and 黄梅戏, and I have seen 豫剧 on TV done film-style rather than stage-style. It was an old and quite dated film-style, but I think it worked quite well and could easily handle some updating. I would also like to see the likes of 豫剧,黄梅戏, and 柳琴戏 get a bit more coverage in foreign writing about China. Everybody knows about Peking Opera, and Kunqu gets plenty of press, but I find 豫剧 and 黄梅戏 (and judging by my first glance, 柳琴戏) to be much more accessible to the Chinese learner.

#7 by Ji Village News on November 26, 2011 - 11:28 am

You reminded me, I actually haven’t watched 《三枪》. Got to check that out and then, perhaps re-access Lao Zhang’s prowess.

There are already 豫剧 version of 《喝面叶》. I haven’t watched that either.

Last year when I was in Beijing, my parents joined me and we went to 国家大剧院 and saw 越剧 《梁山伯与祝英台》. We enjoyed it greatly. Reading the newspaper while waiting for my visa for my upcoming trip at the Chinese consulate this week, I saw a report that price for performances at 国家大剧院 is (or has?) supposed to drop significantly. I hope that is true, and I hope it is part of a trend where people can appreciate, not only art from abroad, but also indigenous art forms, instead of blindly, slavishly worshipping every piece of junk Hollywood concoct together.

#8 by wangbo on November 26, 2011 - 6:51 pm

Now this:

“I hope that is true, and I hope it is part of a trend where people can appreciate, not only art from abroad, but also indigenous art forms, instead of blindly, slavishly worshipping every piece of junk Hollywood concoct together.”

I agree with wholeheartedly.